Australia's Silicon Quantum Computing has chained together 10 quantum dots to create a quantum integrated circuit (IC) able to simulate molecular behaviour.

As proof of the operation of its quantum IC, the organisation used it as an analogue quantum processor, simulating "the structure and energy states of the organic compound polyacetylene", UNSW explained.

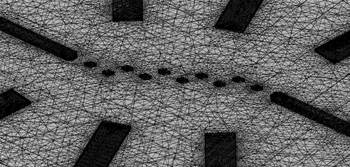

SQC built the processor using a scanning tunneling microscope to precisely place multiple atomic components within a single device at its facility in Sydney.

Among the technological feats SQC says it achieved are the ability to create small enough dots of uniformly sized atoms, allowing their energy levels to align which lets electrons pass easily through them.

SQC was also able to tune the energy level for each dot individually, and collectively, which the company says controls the passage of quantum information.

Distances between the dots had to be controlled with sub-nanometre preceision to keep them close enough yet remaining independent for quantum coherent transport of electrons across chain of atoms.

Founder of SQC, Michelle Simmons - who is also director of the Center of Excellence for Quantum Computation and Communication Technology at UNSW - said the IC is a breakthrough that will allow the construction of quantum models for a new range of materials and pharmaceuticals and more.

The quantum processor SQC built was used to accurately model the quantum states of an organic polyacetylene molecule.

Simmons said that classical computers of today strugge to simulate even small molecules, due to the large number of possible interactions between atoms.

"We have created a superbly precise manufacturing technology that is opening the door to a whole new world," Simmons said.

"It is a huge step towards building a commercial quantum computer."

SQC said work on the processor had started in 2012, and the IC was realised less than a decade after.

Simmons and SQC were inspired by a challenge laid down by theoretical physicist Richard Feynman in 1959, which asserted that if researchers wanted to understand how nature works, they had to be able to control matter at the same length scale as atoms.

.jpg&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)