Several large Australian farms have signed on to be internet of things testbeds, only to find their ambitions thwarted by internet data quotas and IoT systems that don’t live up to their promise.

The challenges of primary producers that have become early adopters of digital technologies were laid bare at Meat and Livestock Australia’s (MLA’s) recent annual digital forum in Canberra.

Their experiences show that Australia must still overcome some significant hurdles before the promises of digital farming and IoT - from connected cows to virtual fencing - can be realised.

And despite the hype around low-power, cellular and satellite networks, in reality reliable connectivity and insufficient data quotas still appear to derail many digital farm ambitions.

“The connectivity that we have been offered across the bush is typical of what we call bush resilience: we put up with it,” beef producer Australian Country Choice’s CEO David Foote said.

“There’s a massive amount of R&D that’s being done and being laid out for us, [but] we can’t apply it in 90 percent of situations.

“I’ve got an operation about 120km west of Toowoomba, so two hours from a major capital city, which has zero connectivity - but I can have it for $264,000 a year if I can get the bloke who owns the biggest tower 15km away to let me rent a space off it. It’s not acceptable.”

Calum Carruth, a co-owner of the 170,000 hectare Murchison House Station near Kalbarri in Western Australia, won’t say how much he spent on a whole-of-farm connectivity system.

He takes his internet from NBN hosted by a friend in town and beams it via a repeater to his homestead; the rest of the station is also covered by a 900MHz network used to run a variety of sensors.

“It’s not exactly cheap but the benefits outweigh the costs by a mile,” Carruth said.

Carruth has only recently started using IoT sensors on the station, noting the technology had finally “matured quite a bit in the last few years”.

“For 20 years people have been promising a lot of things in agtech and not a lot has been delivered,” he said.

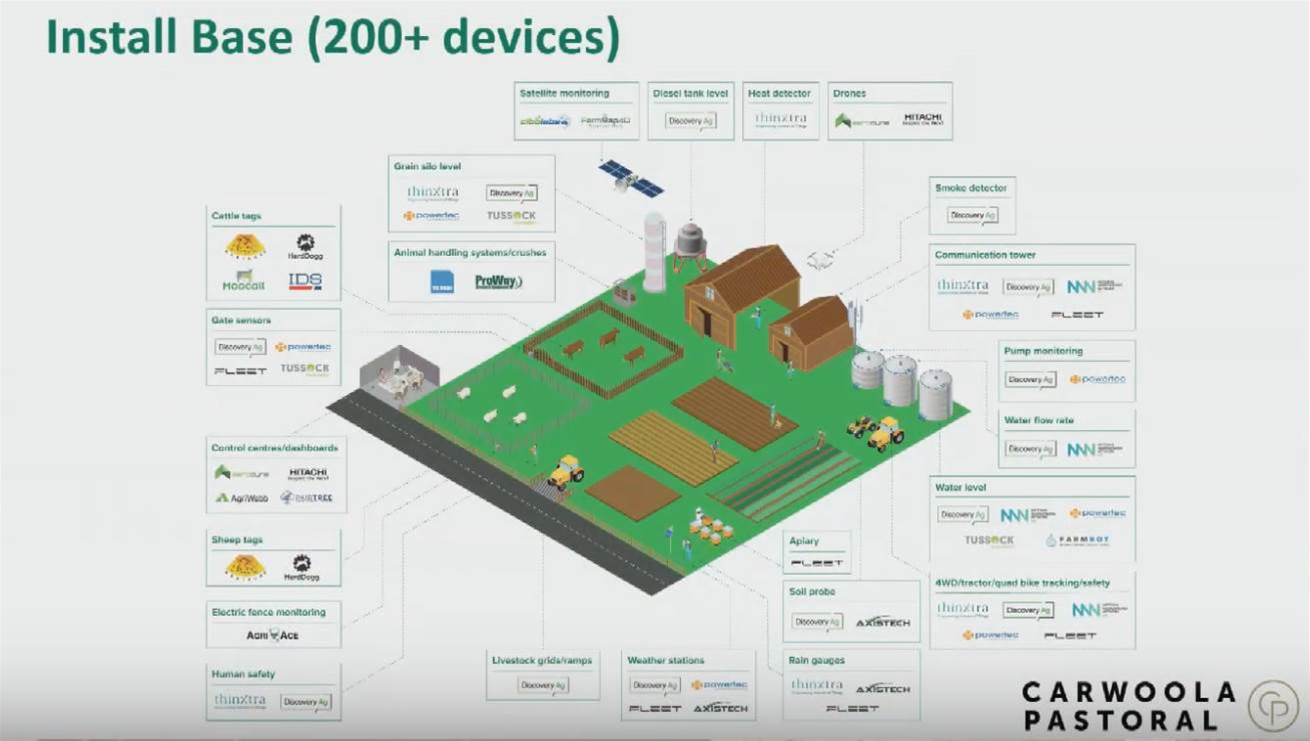

What does - and doesn’t - work in Australian agtech is currently being put to the test at Carwoola Pastoral, a mixed grazing business spread across 6000 hectares and five properties around Bungendore and Queanbeyan, just over the NSW side of the NSW-ACT border.

Carwoola’s project is unrivalled in terms of its scale and yet has attracted little if any attention.

The group of properties under Carwoola Pastoral are testing basically every IoT and connectivity solution they can get their hands on, baking them off against one another to determine what will - and won’t - work in an Australian rural environment.

So far, the properties have deployed 200-plus devices and approached over 150 different companies about their products, but found very few are ready for use.

“Of the 150-plus suppliers that were approached, that were asked to prove [themselves] to MLA and industry ... only 20 have showed up, which I find a little interesting personally but I guess not everyone’s in a position to supply what they say they can or to contribute at a particular time,” Carwoola Pastoral general manager Darren Price said.

“Some of the people that turned up have actually gone away again when devices weren’t quite ready or the challenge of putting them into a commercial farm situation has proven a little bit too hard.”

Price noted that Carwoola has only been using the technologies for a short time, though it appears any return on investment so far isn’t obvious.

“The digital value proposition is an unknown to me at this stage,” he said.

Price is giving the technologies another 6-18 months to demonstrate they are worth the confidence of farmers. After that, Carwoola Pastoral and MLA will create a best practice guide of what digital farm technologies hold the most promise.

Data quota and speeds

A significant consideration for those wanting to get into digital farming is not just the speed of available internet connections but also the data quota they come up.

What’s clear is that neither NBN Co’s Sky Muster nor Telstra’s 3G/4G network - the two most common networks in range - are fit-for-purpose for the needs of a digital farm.

Carruth said that his digital farm uses about 500GB a month - much more “than the 75GB that we were offered from the NBN Co”. Not all of that is for business - some is for his son’s education, or for leisure such as Netflix and gaming. (“I think we deserve it - we work pretty hard,” he says about Netflix use. “Just because you live in the bush doesn’t mean you’re a second-class citizen.”)

NBN Co has made efforts to bump up usage limits, but they’re still below Carruth’s requirements, as are Sky Muster’s speeds, which are well below the 100Mbps he beams in from nearby Kalbarri. Carruth is actually still using NBN, albeit fixed line that he has had to pay to beam from the town to his property.

Annie Brox, managing director of ORIGO Farms, which deployed the network to Murchison House Station, said that the data requirements of producers in Western Australia were “on par with international benchmarks for small to medium enterprises”.

With station-wide connectivity, Murchison’s problems embracing IoT were now firmly around connecting out to the telecommunications network.

“It is the NBN in Kalbarri that is the limiting factor, not the farm network,” Brox said.

“I’m trying to say this to people in the telco industry who blame the last mile as the big problem. The problem here is the speeds to Kalbarri.”

Beef and cattle producer Stanbroke has also run a non-NBN and non-Telstra link to its Chinchilla Feedlot in Queensland’s Western Downs region.

The feedlot supports 40,000 head of cattle and, although only 30 kilometres from Chinchilla, is behind a hill and only had data access via a Telstra 3G connection.

“They had a very marginal signal that dropped out completely for days on end,” said Geoff Marsh, business development director at MarchNet, which Stanbroke now take service from.

“Chinchilla was also in the midst of a coal seam gas boom so 6000 workers were on their doorstep oversubscribing that network as well.”

Like a lot of regional and remote wireless ISPs or WISPs that have sprung up in recent years, MarchNet has made a business out of “creating a telecommunications network where Telstra and NBN Co have not.”

“MarchNet owns and operates facilities to deliver high speed internet throughout regions where all you have access to is an NBN satellite service or some very poor quality 3G or 4G services,” Marsh said.

Stanbroke now has a 50/50Mbps connection between its six homesteads and office and the town. Part of the connection is fibre from a power company, whose capacity MarchNet buys and on-sells.

Marsh notes that the big question from Stanbroke was what they could do if they had good connectivity - thinking about future possibilities was pointless, however, without it.

“The focus of this project with MLA and Stanbroke was to show how solar powered repeater sites along with point-to-point and point-to-multipoint microwave could benefit Stanbroke and the red meat industry as a whole,” Marsh said.

“Once we give them connectivity, what will they do with it?”

Getting proper connectivity - and cost-effectively - remained the biggest hurdle for primary producers.

“The question I’m always asked is not about the water monitoring or the video cameras or the smart fencing or the potential for facial recognition software to recognise wild dogs [on our station] - there’s all sorts of things we can do here - but ... how I got internet at my house,” Carruth said.

MLA’s research, development and innovation general manager Sean Starling called on telcos, governments and others to pick up some of the slack.

“I think one of the striking things there - and we’re seeing it with a few other producers we’re engaging with in this topic - is the 500GB a month of data is about what you need to run these sorts of businesses,” he said.

“Our current mainstream telcos are offering a hell of a lot less than that. So as an industry we need to support our producers more.”

Foote concurs: “All the stuff [vendors say] is real is pointless unless we have affordable connectivity. Think about what virtual fencing means to you - less staff, easier mustering and so on. It is the way of the future but there’s no one thinking about giving us the connectivity to do it.”

Opportunities are there

Those that have footed large bills for reliable connectivity are able to see some benefits from IoT and sensor networks.

Murchison House Station has deployed a water monitoring system in phase one of its IoT deployment.

“It will control all tanks with flow meters and level switches,” Carruth said.

“Instead of a 250km drive three times a week to check our waters, I should simply get an alert on my phone when anything drops below normal.

“Even in its first phase, the vehicle maintenance savings I think will be significant, and that’s without including the fact that we can target our staff’s work instead of sending them off on a Sunday drive to just check out what’s going on. The future is here and we’re making it happen right now.”

A lot could be read from even a little bit of water monitoring data - and Carruth’s system is designed to report water levels across the station at one-minute intervals.

“It’s so easy to use that I’ve gone away from the idea of trough sensors altogether. We just use an outflow on the tank - and I can see when a couple of bulls come in to drink in the afternoon because 250L of water will go out and then it stops,” he said.

“Once you get used to seeing that pattern of drinking at your trough, if that flatlines, either you’ve lost your cattle or your trough’s got no water in it so you head out and check it.”

Carruth said that some trips to water troughs still had to be made: “you’ve got to go out there and scrub the trough every couple of weeks”, he said.

However, he believed the water monitoring system would save $25,000 in the first year alone, and “that’s without factoring in my workers can do something else instead of trough runs.”

Carwoola’s Darren Price has an ark’s worth of IoT technologies.

“This is a list of the solutions that have been installed across our business in the last two or three months,” he said.

“We have monitors for troughs and tanks and dams, weather stations and rain gauges, diesel tank monitors, soil probes, sheep and cattle tags - some smarter than others, gate and cattle ramp monitors, we have some digital mapping, electric fence monitors, smoke alarms and shed condition monitors, vehicle and asset tracking, farm management software, apiary devices, drone technology, cattle heat detection, silo level monitors and animal handling systems.”

Carwoola's installations clearly need more time to demonstrate value; already, though, some of the challenges for the IoT industry and farmers hoping to go digital had become clear.

Aside from the vast number of solutions that were clearly not commercially ready - despite the vendors thinking otherwise - Price had found IoT was also not nearly as simple as it was sold to be.

“What we did find amongst all the things that were installed or that we were approached to install is that it’s not just as simple as buying something off-the-shelf - there’s quite a bit of infrastructure that needs to go in with the devices and a lot of stuff in the back-of-house that needs to be done to make the data meaningful to you when you do receive it,” he said.

“There’s also hidden costs in fees around communications and so forth and infrastructure costs to protect the devices.”

Price also wanted to see different providers able to interoperate, particularly when it came to data collection.

“We need providers working together. Sharing data is a massive thing. There’s no point in me having 200 devices installed and 55 apps or different platforms reporting to me. I need to have the ability to look at a single platform that is meaningful to the staff and owners of the business,” he said.

Still, Price saw the potential of IoT on Australian farms, even if the process was still a bit painful.

“It’s not necessarily a cheap option to install digital tech on your farms but if you choose the correct direction and devices, the money would appear to be well spent.”

.jpg&h=140&w=231&c=1&s=0)